Exterior Siding vs Interior Paneling Grade and Installation Tolerance Differences

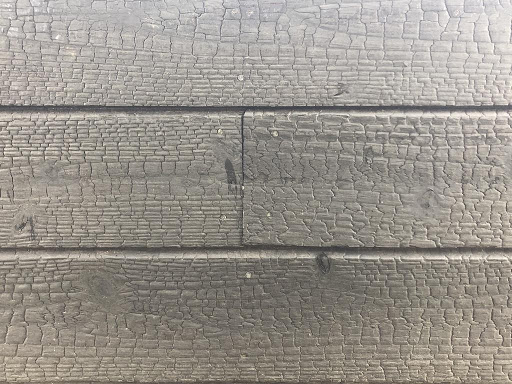

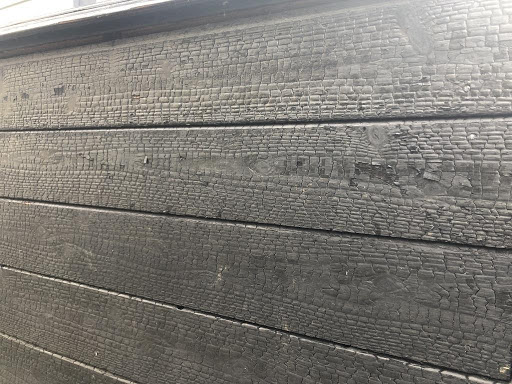

Holed up during the pandemic this weekend I was at home thinking about blog content ideas and what would benefit our customers the most to share. One of the FAQs on our website is along the lines of “What else should I know about yakisugi” so we’ve thought about it previously. On that thought, it is good to share technical carpentry grades and tolerances with owners and designers, so this post is for that purpose. The photos are from my house.

Architects need to plan for some variation when using natural materials, and owners need to understand that there are various grades of construction and that in the end it is just a house. Exterior cladding is viewed from several feet away, and interior woodwork is touched and looked at close up. Exterior wood will get dirty and move, interior woodwork will remain in appearance as originally installed. Material and installation is therefore different between the two application categories.

A lot of people have the conception that yakisugi is a fancy, high-design, expensive building material. In reality, historically through today it is primarily considered an affordable siding material for the masses. Professor Fujimori, Japanese building materials historian and current Director of the Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum, told me that modern architects consider yakisugi a substandard material. Wood structural longevity, consistency, color longevity, fire resistance, etc., will never match brick or aluminium cladding options. Natural materials are by nature less consistent than man-made materials. Testing and certifications are more challenging for natural materials, so project engineering and plan review are more limiting than with engineered materials.

In any case our core market is low-rise construction, which wood siding is a perfect match for. Yakisugi is also being used more in interior applications in the West, since there is not common understanding that yakisugi is an exterior cladding material (it is only used for interior applications traditionally only on ceilings as a carbon air filter). So yakisugi is manufactured to exterior grade finish and dimensions. The traditional millwork, drying protocol, and heat treatment will still produce straighter sticks than standard cedar or pine siding, but it is not milled to the precision of interior millworks such as crown, flooring, or other moulding , and is dried to a different standard moisture content.

Exterior cladding is dried to 10-15% moisture content, and interior wood is dried to 6-9% moisture content. Exterior siding must be straight in long lengths, move consistently when exposed to atmospheric changes, dry out quickly when it gets wet, and look good. Interior millwork must be very dry, color and grain very consistent, and millwork repeated to high precision.

A standard rule of thumb in the carpentry world is that standard framing tolerance is within 1/8” of plan dimensions and up to 1/8” gap at joints, and trim carpentry is to within 1/16” of plan dimensions and up to 1/16” gap at joints. Another rule of thumb for appearance-grade woodworking, including exterior siding and interior woodwork, is that tolerances are to either paint grade or stain grade, which similarly breaks down to about 1/8” and 1/16” tolerances respectively. Depending on project budget, tradesperson skill level, and customer expectations, the grade of materials and quality of installation varies dramatically.

In traditional carpentry, the tradesperson does the best they can to achieve long term functionality and best appearance for what they’re given to work with. With siding and paneling there is a standard sweet spot for tolerances as mentioned above. Due to atmospheric moisture, UV load, and temperature variation according to season, time of day, geographic location, and site design and orientation, exterior siding is a challenging application for wood. Wood siding statistically has the best Life Cycle Analysis when compared to other cladding options, but it moves a lot since a natural, breathable material fully exposed to the weather.

Depending on conditions, siding moisture content can range 5% to 35%, surface temperature cycles the full atmospheric range, and each field’s UV exposure changes ongoing over the course of each day. Temperature and moisture content cause the dimensions of siding to change, and porous softwoods are generally used for siding applications since they move less due to atmospheric fluctuation (they also are used since they dry out quickly, which results in less propensity to rot). Exterior siding is going to move no matter what, so the cladding must be milled to minimize dimensional movement, and installed in a way that looks good and lasts a long time despite the movement. Fastener schedule should also be more robust and the finishes must be optimized for fungi resistance, UV protection, and breathability.

Yakisugi by definition is always milled to exterior application parameters including specific resawn patterns and drying protocols, heat treatment under controlled conditions, and then finished with exterior grade oil finishes. There is a huge range of dimensional movement species to species and location to location in exterior applications, but for our exterior products, stain-grade yakisugi and KD sugi, the general rule of thumb is movement of 1/8” each dimension in terms of plank length and plank width. This means that the planks are manufactured under a protocol that minimizes dimensional movement to about this much during the entire range of exterior exposure conditions. Interior millwork is not exposed to the same harsh conditions, but must be milled to higher precision and be dried under different protocol so that it does not move during much lower moisture content level fluctuation. Stain-grade interior woodwork should not more more than 1/32” or 1/16″ depending on location and species. Think about flooring and how it is unacceptable to see gaps over time due to shrinkage.

The installation parameters are similar. First of all the wood must be acclimated to site equilibrium moisture content, which varies dramatically location to location. The install will be to tighter tolerances if the wood is stickered or scattered at the jobsite until it stops moving. In my experience 75% of the movement occurs during the first week on site and another 20% in the second week. The final 5% might take a month or more. This is true for both exterior and interior site acclimation, but really is more critical for interior due to being so dry. It is also more critical in drier climates or when the wood is treated with a hydroscopic fire retardant (which are basically borate salt that absorbs atmospheric moisture).

The next important parameter is installation over a screen wall and with headed, ring-shank nails. Without a screen, temperature fluctuation will be more dramatic and therefore the planks will move more. Headed face nails allow the wood to move and then return it to original position. They can also be tightened up in the future when the wood starts to pull them out, whereas pin or casing nails or staples will tear through the softwood plank as it moves from exposure.

Most stain grade siding is installed with 1/16” tolerances, compared to 1/8” tolerances for paint-grade. This is important since gaps that open up as the weather changes and the wood dries should not be more than 1/8” in order to be acceptable in appearance for most owners. Interior applications are much easier since the wood won’t move after install. The wood can be pinned and glued straight to the substrate.

For our product another difference between exterior and interior grades is oil finish appearance variation and blemish acceptance. With exterior siding, it is completely fine for there to be inconsistency in sheen due to the entire range of penetration and flashing during oil application and drying (“flashing” means the oil becomes glossy from puddling or inconsistent penetration). The oil needs to penetrate so that it doesn’t wash off, and there needs to be more surface residue for UV protection in order to achieve better color longevity. So for exterior finishes we apply a large volume of oil in less coats, which creates more sheen variation. Since viewed from farther away and lower per-square-foot budget allocation, exterior siding can be blemished such as from abrasion or chud glued to the face by the oil finish (“chud” is solid pieces such as sawdust, soot, fiber, or dirt that get into the finish while oiling or painting). For interior applications sheen variation and adhered chud are generally not allowed.

At the end of the day despite all the levels of OCD or nonchalance during construction, a finished project is meant to be used by the owner. It’s just a house there for the utility of the owner. Corners will get boogered up, fields will get scratched, colors will change, gaps will open up, etc. Wholesome, high-quality materials and careful installation will look good over the decades or centuries, so don’t fret too much. Think about how beautiful patinated chateaus in Loire, villas along the Mediterranean, Victorian or Craftsman houses in North America, or Taisho and earlier houses in Japan all are. Get the project done and use it, and appreciate the utility as it weathers and changes over time.

Leave a Reply